From : opendemocracy.net

French anti-nuclear activists explore whether targeted direct action, including the deliberate use of the court system to launch political challenges, can open up a space for democratic participation

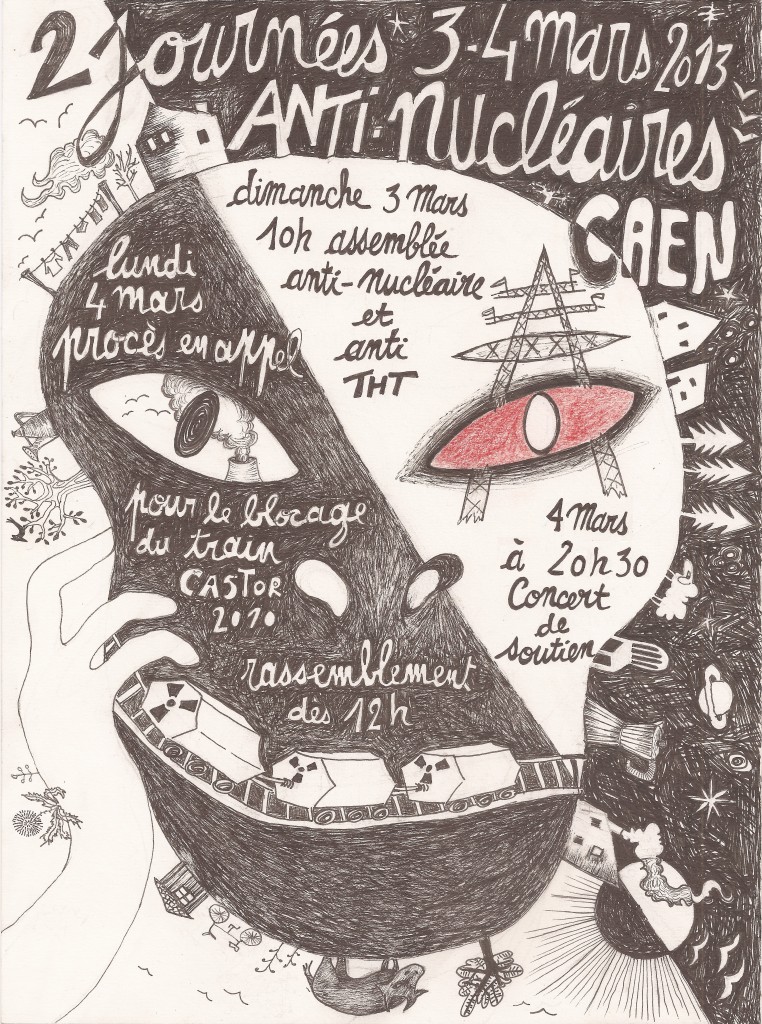

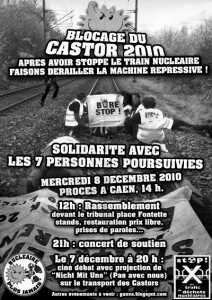

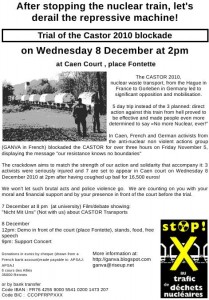

On 5 November last, a train carrying vitrified nuclear waste left Valognes, in northern France, heading for Gorleben, in Germany. A little after half past three in the afternoon, as the train drew into Caen station, a young woman alerted the driver to the presence of half a dozen people on the line. As the engine drew to a halt, five of the six – all belonging to a small affinity group named GANVA, or non-violent anti-nuclear activist group – chained themselves to the track and to each other. This was the first blockage in a journey constantly disrupted by anti-nuclear activists, especially in Germany. In Caen, it took the police three and half hours to remove the activists from the track, and enable the shipment to continue a journey that eventually took 91 hours, mobilised 20,000 police, and cost a reported 50 million euros. These actions clearly caused great embarrassment to the French and German governments, and attracted global media attention. But is that all they achieved? Do actions such as this simply testify to the impotence of citizens when faced with the nuclear prerogatives of states, or is there a possibility here for something more positive, more democratic to emerge?

The costs of action

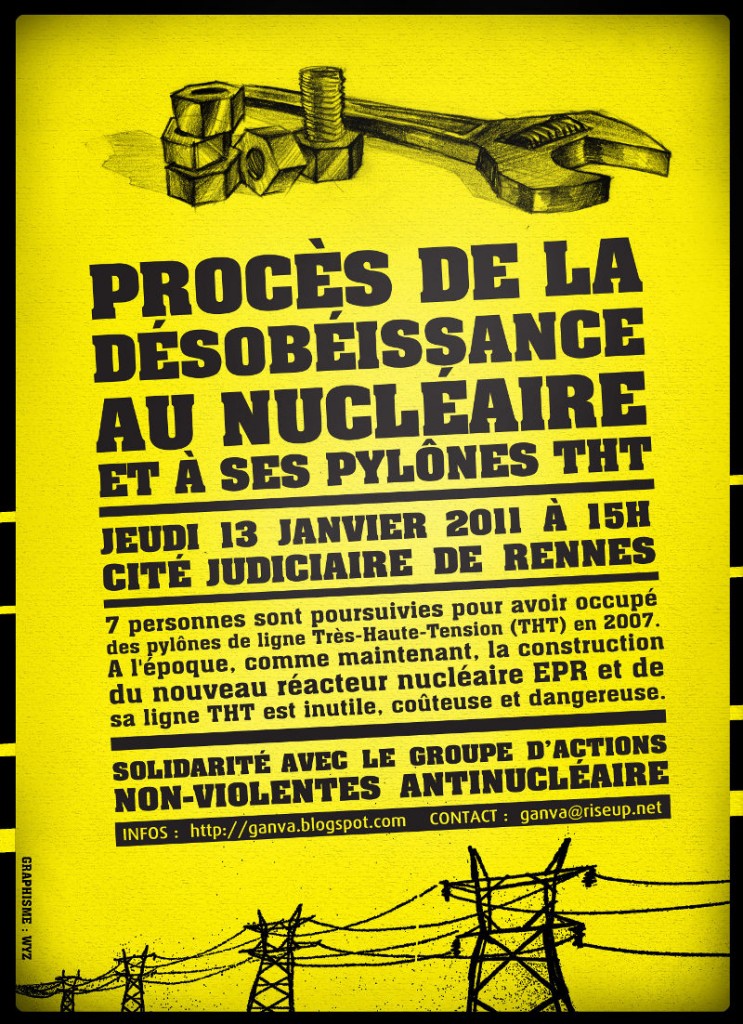

Four weeks ago, on December 8, the action reached court in Caen, as all seven activists were tried for obstructing the railways under a law dating back to 1845. Outside the court building, about three hundred activists occupied the road, with stalls, musicians, banners, speeches, and television crews. Numerous organisations – environmental, rights, anti-nuclear, far left, libertarian, syndicalist – came to demonstrate their support. Inside, the wood-panelled courtroom was packed with supporters, including a small group from Germany. The Ganva is used to this type of action, having already stopped a nuclear waste train in Normandy in July 2008, and carrying out a series of occupations of electricity pylons the previous spring, again protesting against nuclear policy. The group has adopted a structure without formal organisation, both to make it more flexible and to protect it from the possible seizure of funds by court decision. This time, not only has the state prosecutor called for significant fines to be imposed (of 2000 or 3000 euros per activist), but the SNCF has demanded upwards of 40,000 euros in compensation, and the activists were obliged to post a guarantee of 16,500 euros against their liberty ahead of the court hearing. There are other costs. The police’s approach to releasing the activists’ arms from their steel tubes left two with serious burns to their hands and a third with two sliced tendons on his left wrist. The state prosecutor has demanded suspended prison sentences for all seven activists, six of whom have no previous offences, and one of whom has only a trivial fine on his record. The prosecutor also demanded that one of the activists, C., have the offence placed on her criminal record – effectively ensuring that she would lose her job as a supply teacher in the state education system. All of the activists are young, and all of them are unemployed, studying, or in low-paid jobs.

If being prosecuted is to make sense as political action, then the prospect of being maimed by power saws, taken to court, being fined, losing one’s job, and undergoing considerable emotional stress, also has to offer collective benefits. This could be located in the direct effects of the action itself – but there is a sense in which, taken narrowly, stopping a nuclear waste train leaving La Hague is an idiosyncratic gesture. La Hague treats nuclear waste so as to remove plutonium, to be recycled for potential use in nuclear weapons; it would make more sense to stop waste trains arriving rather than leaving. Most environmental organisations, including Greenpeace, accept the principle that nuclear waste should be stored in the country of production, in this case Germany (though Gorleben is not a storage facility either).

Building political capacity

So why undertake this sort of action? Prosecution for this sort of offence provides two sorts of opportunity for activists. The first is to build solidarities: trials are chances to display collective identity, to reinforce existing and create new ties – particularly, perhaps, where state responses are considered to be disproportionate, creating what social movement scholars call ‘backfire’, where the severity of repression generates public sympathy. The second opportunity is to create arenas for democratic challenge. ‘Have mass mobilisation, and public information, advanced the debate on nuclear power? Of course not’, asked the defence rhetorically during the hearing. Throughout the trial, prosecution and defence were constantly engaged in a contest to define the process underway: for the prosecution, to restrict debate to the bare facts of the action (themselves uncontested by the defendants), and thus to consider its motivation in strict legal terms; for the defence, to generalise, to draw the debate into political terms, establishing motivation as democratic dysfunction, as the opposition between a nuclearised society and participative citizenship:

C.: Our goal is to create a real debate about nuclear power, the public has never been consulted.

State prosecutor: It’s not in court that that type of debate can take place, but within the democratic organs of society. You are here to be judged for your actions, not to make the world anew.

C.: That’s exactly why I am here.

The use of the courts to make political arguments and launch challenges to public policy has been a feature of a number of recent campaigns in France, from anti-advertising to anti-GMO groups. The Ganva is at least partly inspired by the latter, whose persistent direct action has rendered the cultivation of genetically modified crops in France practically impossible. It is unlikely the Ganva will win their case when the decision is handed down on 26 January; it is also unlikely that the heavy sentences demanded by the state prosecutor will be acceded to, for activists with clean records acting non-violently, openly and publically for political reasons. Beyond the detail of the judgment, what is interesting is the attempt of activists to think of ways to open up a viable democratic space, to create the conditions for citizens, through public action, to become subjective actors in the determination of social choices. In the face of the closure of debate over nuclear policy, direct action attempts to create an arena to ‘speak truth to power’, or at the very least to confront it, within existing institutional arrangements, with a different vision of process and politics.

Direct action and mass mobilisation

The Ganva’s action thus offers a potentially important way of thinking about strategies for expressing citizenship where public choices are taken remotely. But this type of action also has clear limits. The anti-GMO campaign has been successful because it enjoys mass support, charismatic leadership, and institutional access. It is unlikely the Ganva can replicate this type of success: the group does not have the capacity or opportunity to commit widespread actions; for the moment has little appetite to adopt a repeat offender strategy which worked so well for the anti-GM movement by forcing the courts to imprison activists; and nuclear policy, strategically central to energy and diplomacy in France, is less likely to be the subject of tactical government concessions. Most crucially, despite the defence’s rhetoric, it is difficult to see direct action working effectively as an alternative, rather than a complement, to mass mobilisation. And though mass mobilisation has produced successful results against nuclear power in the French north-west, this was against new plant-siting decisions, a generation ago. These conditions are currently lacking.

But the recent movement against pension reform in France, though in the end unsuccessful, was also noticeable for the greater role played by direct action than has recently been the case in waves of strikes and demonstrations – through the blockages of oil refineries, bus depots, major road routes. In the absence of governmental responses to mass mobilisation on its own, it may be in the more fully realised integration of mass mobilisation and this type of targeted direct action, including the deliberate use of the court system to launch political challenges, that effective strategies for creating democratic participation lie.

About the author

Graeme Hayes is a Marie Curie research fellow at the CRAPE research centre, Institut d’études politiques, Rennes, France.